Managing and Mending Woman

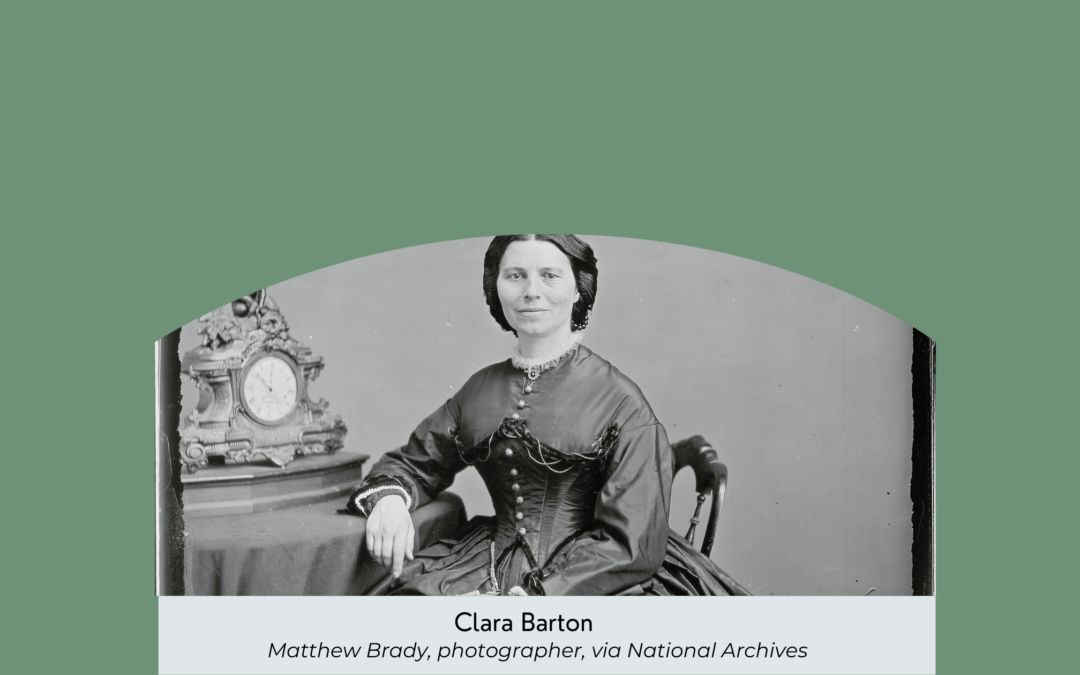

Can you remember the first time you learned about Clara Barton?

She has recently shown up in a mini-series and most people probably just nodded and thought, “Of course, Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross.”

Did you know that she was also a patent office clerk? Seems that being paid the same amount as her male colleagues was quite the problem – and a first for a female government clerk. Yet being in Washington, D.C. at the outbreak of the Civil War put her in the right place at the right time to find her life’s calling.

As we watch images of refugees leaving Ukraine in the latest of the world’s conflicts, someone like Clara Barton springs to mind — someone with an incredible knack for organization, skill at tending to the wounded, and, importantly, raising the funds to do the work.

A recent piece on Marketplace focused on how best to help those fleeing Ukraine mentioned, yes Clara Barton, who handed out cash in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War.

Wait – she was even helping in the Franco Prussian War?

Take a few minutes to read a bit about her life.

She was painfully shy as a young girl, but when did she feel most comfortable? Helping others.

She got rather good at it.