by Kate Evert | Sep 12, 2022 | Jobs, Leadership, Leadership Agility, Pivoting

In the autumn of 1984 when I arrived in England to begin an academic year there, I wasn’t thinking so much about Queen Elizabeth II. There to study Tudor and Stuart History, I had Elizabeth I on my mind. What a strong, and amazing monarch she was! As an American, the thing I most noticed about Elizabeth II? Seeing her image on a daily basis: on stamps and on money. That was odd to me, we enlightened Americans had a tradition that no living person should be on its currency.

In September of 2015, I was in the UK when Her Majesty surpassed Victoria and became the longest reigning British monarch. Older, and having seen more of life, commitments, and oaths, I was grateful to be there on that historic day. I had grown to respect her greatly for her endurance and dedication alone. The James Bond video only added to my admiration.

In 2018 circumstances found me sitting in on a college seminar class called Gender in Politics. That day, one topic of conversation was Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister of New Zealand. The students and professor turned from discussing the job she was doing, to how many countries have had female leaders. Why, they wondered had the United States yet to have a female president? One student posited that countries that had had monarchies might be more comfortable with a woman as a leader.

The conversation continued around this theme. How rich the irony that this discussion might be praising benefits of an “outdated” form of rule?

September 2022. Surveying some of the coverage of Queen Elizabeth II’s death, I stumbled across a BBC interview of four women who had travelled to lay wreaths at Buckingham Palace. One of the women said: “We will never see a queen again, and that is quite odd.”

For that group, every single day of their life, there was a female leader, always adorning their stamps and their money. Indeed, throughout the Commonwealth, especially with the advent of television, and now social media, a huge population has grown up with not only a female head of state, but one that demonstrated duty that few others on earth will ever equal.

Elizabeth I was indeed an important monarch, solidifying England’s position at tumultuous time. Elizabeth II was given a far trickier portfolio – of acknowledging that the sort of democracy that had evolved in Britain over centuries was worthy of export, that the Empire should disassemble, and that she would shepherd the process with grace and dignity.

by Kate Evert | Feb 2, 2022 | Covid-19, Future of Work, Human Capital, Inspiration, Pivoting, Productivity, Strategy

Those of us of a certain age, grew up when Groundhog Day only meant one thing: one day in February when kids, especially, waited to see if there was a chance of an early spring.

Since the early 1990s, the phrase has taken on a new meaning, a day that seems to repeat over and over again … without end. In the spirit of that NEW meaning, we are rerunning last year’s February 2 Blog …

If Covid had a mascot, it would be the groundhog, at least in the United States. Various animals in different northern regions have stuck their necks out to foretell if winter is over. Every year on February 2, many cultures look for a sign that winter might end.

Recently, a podcast caught my attention; hadn’t hit start, hadn’t heard of the book, but who wouldn’t keep listening about a book called Wintering when it is January in the snowy North? The author, Katherine May, read a passage:

“Plants and animals don’t fight the winter; they don’t pretend it’s not happening and attempt to carry on living the same lives they lived in the summer. They prepare. They adapt.”

Suddenly you recall an Aesop’s fable, of the Ant and the Grasshopper. One creature is busy storing food for the cold weather, one plays in the sun and does not. You probably first heard this tale at about the age of five, and Aesop wrote, or at least recorded it, 5,000 years ago.

In her interview, the author says she feels that Covid has been one L O N G Wintering. Many of us have forgotten how to winter—how to store away preserves in our cellars for the seasons in which the harvests are not plentiful. Companies either don’t retain earnings for a rainy day or are pressured to pay them out to shareholders.

This February 2, the groundhog represents us emerging from our Covid Hibernation, looking for hope, an efficient vaccine distribution system, some semblance of normal. As we all know we will have at least six more weeks of Covid Winter, but perhaps we can resolve to prepare a bit more for our next “wintering”—whatever it may be—so that we might be more prepared, like the ant, and not have to go underground, like the groundhog.

by Kate Evert | Oct 12, 2021 | Corporate Culture, Creativity at Work, Future of Work, Human Capital, Human Resources, Innovation, Labor Markets, Leadership Agility, Management, Performance Management, Pivoting, Productivity

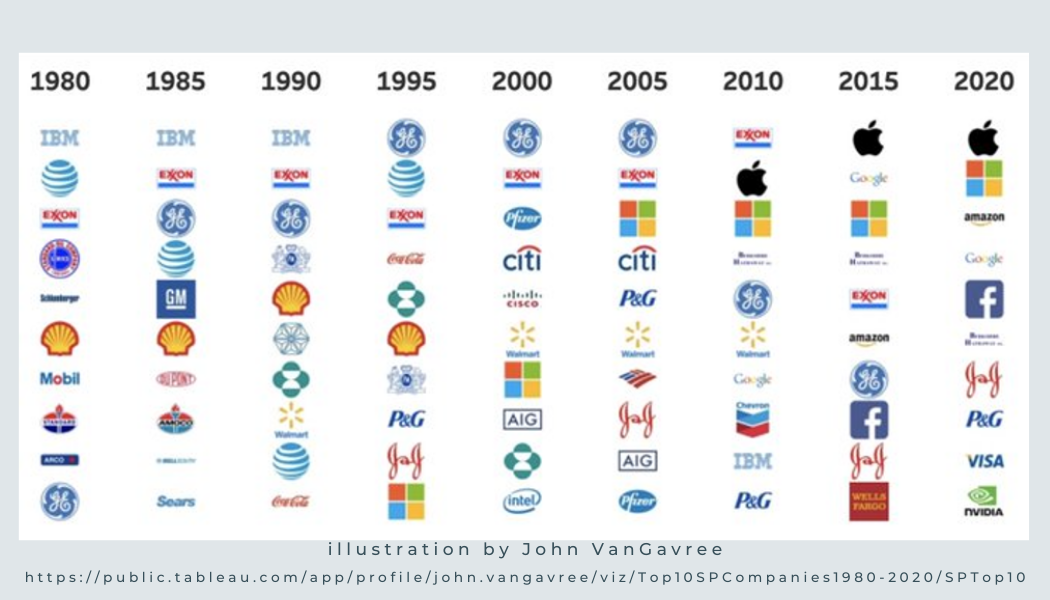

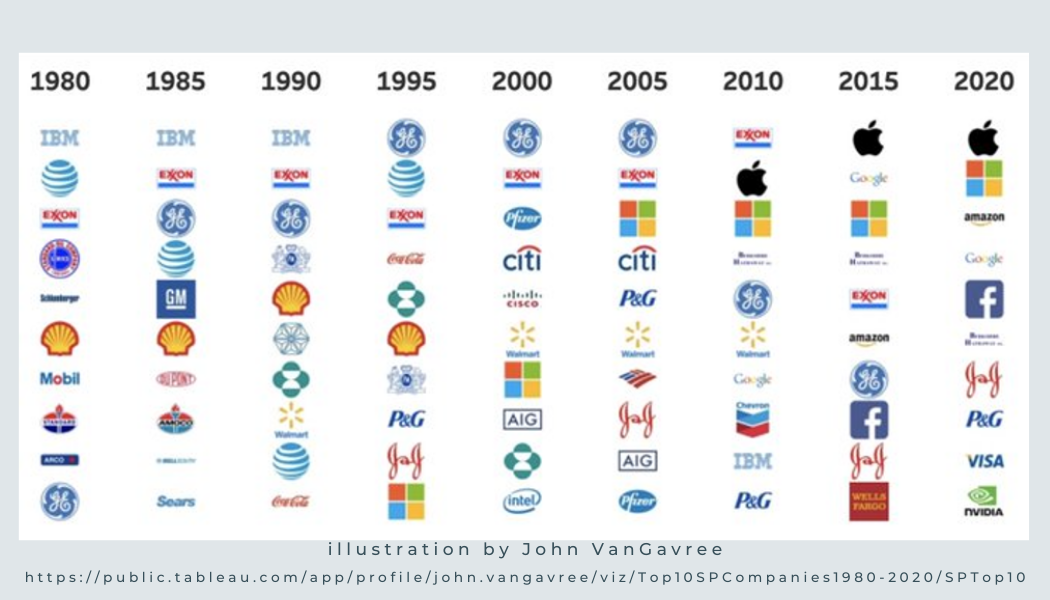

This chart is eye grabbing.

Most reading this blog will easily recognize the vast majority of these logos. You aspired to work at some, you DID work for some.

One logo immediately caught my eye. In my days as a credit analyst, I signaled they were facing headwinds. In return, I got an extreme dressing down. The summation of that boss’s lecture? They were one of the largest companies in the country so how could I possibly even think to suggest that they were anything but stable?

The companies that have fallen off of this chart have done so for various reasons, for some it was hubris, for others an inability to pivot, in other cases, tastes change. A lack of innovation led to the demise of many.

Just yesterday, Jack Kelly had a piece in Forbes about the ultimate innovation: tailoring jobs to the individual needs of the various workers. Given the current labor and talent shortage in the U.S., this is exactly the right sort of solution for many organizations.

When firms can keep a clear focus on the deliverable, the output, where or how something gets done is less important.

Kelly says:

Consider how much better work would be if managers held conversations with their team, actively listened to how they’d like to work and then designed the job around their needs. Morning people could start early. Night owls can begin later in the day.

I lived this. Over 20 years ago at PwC, we had a well-oiled team that knew each other’s bio-rhythms and peak productivity hours. We joked that there were probably only three hours that someone from our group wasn’t awake and available; one person was an extreme lark that got into the office at 5:00 am, while another was such an extreme night owl that we regularly got emails from him at 2:00 am, working remotely. That is when I started experimenting with working from home … which one secretary dreaded because in uber-efficiency mode I banged through my To Dos, which then required her involvement.

As so many HR experts have reiterated: there are two ways to measure performance – inputs and outputs. Do you want to measure the hours that you see someone in (or their jacket on) their chair? Or do you want to measure what they deliver? The RESULTS.

Go back to that left hand side of the graphic. What happened to the temples those companies built? Big Stan in Chicago? GE Headquarters in Connecticut? The Sears Tower? They filled up with employees each morning and emptied every night.

Big buildings don’t matter. That S&P graphic is based on results.

by Kate Evert | Jun 15, 2021 | DEI, Leadership Agility, Performance Management, Pivoting

The headlines are filled with articles about the return to work, specifically, getting people back into an office. Some of the articles then focus on subtopics such as dress codes, flexible schedules, and mandatory vaccinations. At the core of these articles is an underlying assumption that either companies want to treat everyone the same, or feel that they must treat everyone the same.

With all of these articles swirling in my head, I reflected on the kudos given to Red Auerbach. Reading the autobiography one of his protégés, who also became a coach, I have been introduced to his genius, his legend, and his insights on people. “I’ve never been around a man who managed … better than Red Auerbach. Particularly, the egos he had to deal with, the cross cultures he had to deal with and all the variations in the kinds of people that I saw him be associated with.”

That’s when it hit me that this is why the world of management has its collective basketball shorts in a twist.

The typical manager does not have a team any bigger than Red did when he led the Boston Celtics to nine championships. If Red could find a way to coach, cajole, badger, and encourage his players … here’s betting today’s managers can. Of course, just as Red needed to comply with NBA guidelines, today’s managers must not run afoul of the pertinent HR laws that pertain to their team of employees.

Stat sheets don’t lie, and a manager who sets clear goals will know quarter by quarter who is performing.

by CHRC | Feb 2, 2021 | Covid-19, Future of Work, Human Capital, Inspiration, Pivoting, Productivity, Strategy

If Covid had a mascot, it would be the groundhog, at least in the United States. Various animals in different northern regions have stuck their necks out to foretell if winter is over. Every year on February 2, many cultures look for a sign that winter might end.

Recently, a podcast caught my attention; hadn’t hit start, hadn’t heard of the book, but who wouldn’t keep listening about a book called Wintering when it is January in the snowy North? The author, Katherine May, read a passage:

“Plants and animals don’t fight the winter; they don’t pretend it’s not happening and attempt to carry on living the same lives they lived in the summer. They prepare. They adapt.”

Suddenly you recall an Aesop’s fable, of the Ant and the Grasshopper. One creature is busy storing food for the cold weather, one plays in the sun and does not. You probably first heard this tale at about the age of five, and Aesop wrote, or at least recorded it, 5,000 years ago.

In her interview, the author says she feels that Covid has been one L O N G Wintering. Many of us have forgotten how to winter—how to store away preserves in our cellars for the seasons in which the harvests are not plentiful. Companies either don’t retain earnings for a rainy day or are pressured to pay them out to shareholders.

This February 2, the groundhog represents us emerging from our Covid Hibernation, looking for hope, an efficient vaccine distribution system, some semblance of normal. As we all know we will have at least six more weeks of Covid Winter, but perhaps we can resolve to prepare a bit more for our next “wintering”—whatever it may be—so that we might be more prepared, like the ant, and not have to go underground, like the groundhog.

by CHRC | Oct 15, 2020 | Corporate Culture, Creativity at Work, Fail Forward, Innovation, Leadership, Pivoting, Strategy

… smarter than you think. – A. A. Milne

But perhaps only if you work in the right environment?

It is an environment in which the best leaders are going to foster, sustain, and reward innovation.

Yet easier said than done for leaders for whom this is a whole new paradigm. So, imagine the thrill when the Harvard Business Review published a wonderful “how to” article this week. The article not only reinforced the theme of last week’s blog—but the author was clever enough to give seven concrete ways to create the kind of environment in which people are going to feel comfortable taking chances. Experimenting. Improvising. Innovating. Being Creative. All the things that the Autumn of Covid requires.

The author, Timothy R. Clark, announces at the outset of his article that once you stop innovating, you die. He dubs the required culture one of Intellectual Bravery, a superb concept and phrase. Who is responsible for creating, cultivating, and sustaining this culture? The leader.

All seven of the techniques or behaviors he points out are wonderful, but if you could only do four, CHRC prioritizes these:

- Take your finger off the fear button – credit once again to John Cleese; sorry, Machiavelli

- Assign dissent – rotate the role of Devil’s advocate

- Model vulnerability – if a leader cannot do this after the last seven months … question his humanity

- Weigh in last – Probably the most valuable tactic of all. As consultants we have watched an entire day’s worth of desperately needed information and input get instantly silenced by a leader who airs his opinions first.

History rewards the brave, and apparently, so does innovation.